In the materials laboratory, if there is one piece of equipment that is both ubiquitous and crucial, the blade coater certainly earns its place. It appears simple, is straightforward to operate, yet serves as an indispensable "coating specialist" in numerous research fields such as electrochemistry, batteries, and sensors. The principle of the blade coater is quite straightforward: a blade with adjustable height spreads the slurry evenly onto a substrate, forming a thin, uniform film. This process may sound akin to manual gluing, but the machine ensures greater precision and controllability. In battery electrode fabrication, for instance, the slurry—a mixture of active material, conductive agent, and binder for common lithium-ion battery cathodes—requires this machine to be coated onto aluminum foil, forming a uniform electrode layer.

Its advantages are evident: flexible operation suitable for small-batch, multi-formulation experimental research; precise control over coating thickness via blade gap adjustment, ensuring good reproducibility; simple device structure, easy maintenance, and cleaning, accommodating the variable needs of a laboratory. For many students learning electrode preparation, the first lesson often begins with using a blade coater. Although more sophisticated techniques like spray or spin coating exist, blade coating remains a viable method for many research groups at the laboratory stage. However, it is not without limitations. Blade coating imposes certain requirements on slurry rheology; slurries that are too dilute or too viscous can affect coating quality. While it offers better uniformity over large areas compared to manual methods, it still falls short of industrial coating equipment. Post-drying, the coating may require subsequent processes like calendering to achieve ideal density and conductivity. Thus, it functions more as an "experimental transition tool," aiding researchers in rapidly validating material formulations and process windows.

In practical use, the blade coater is often integrated with equipment like slurry mixers, drying ovens, and calenders to form a complete small-scale electrode fabrication workflow. Many graduate students interact with it daily—adjusting the gap, setting the speed, cleaning the blade, handling substrates... While these tasks may seem repetitive, each step influences the subsequent performance of the battery.

With prolonged experience in the lab, one realizes that different models of blade coaters correspond to different "crafts." If you find yourself overwhelmed by the numerous "Huinuo" brand coaters on the Nanbeichao mall, don't worry. The core principle for selection is similar to choosing any tool: it depends on the tasks you most frequently perform.

First, clarify your "daily tasks":

Are you primarily coating battery electrodes (where the slurry is viscous, requiring uniform and stable thickness), optical films (requiring ultra-thin, defect-free coatings), or conducting spread tests for adhesives or paints? This directly determines the essential capabilities you need.

Next, consider these key aspects:

Coating Head (Blade/Coating Rod): This is its "hand." If your slurry contains particles, or if you require extremely precise thickness control, look for models offering micrometer-level precision in gap adjustment, some featuring micrometer screws for a feel akin to adjusting a microscope. If samples are prone to scratching (e.g., soft polymer films), you may need a machine compatible with coating rods of different materials (like stainless steel or glass).

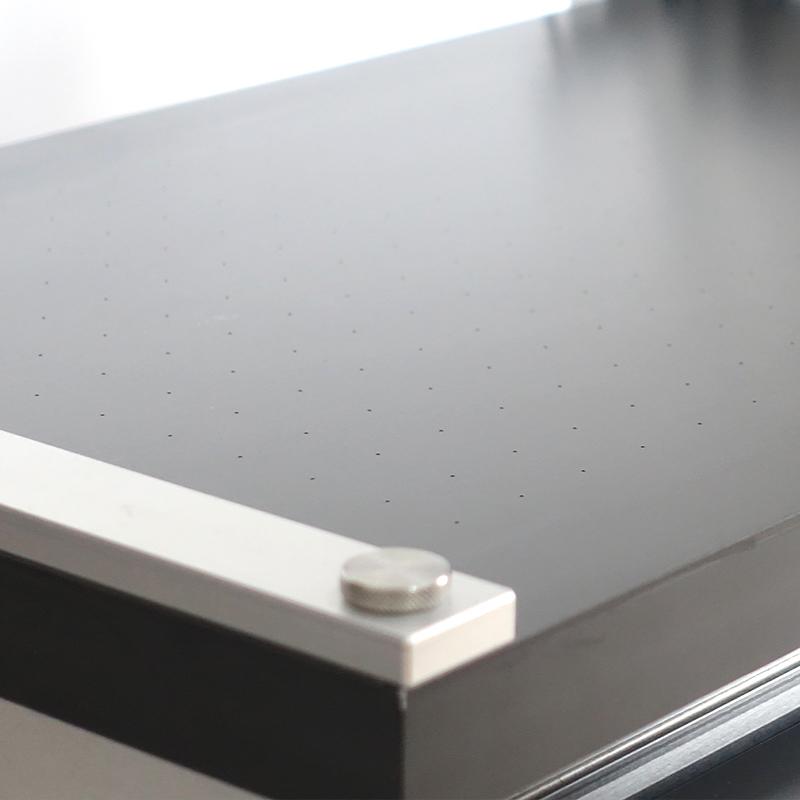

Substrate Stage: This is its "workbench." The most common type is a vacuum adsorption stage, resembling a perforated plate that flattens aluminum foil or films when activated—crucial for achieving uniform coatings. If you frequently use rigid substrates (like glass or silicon wafers), ensure the stage is flat and has suitable clamps. Some advanced models feature heated stages, allowing for preliminary drying immediately after coating, which is particularly useful for materials with highly volatile solvents.

Level of Automation: This ensures "steady hands." The most basic models require manual adjustment of coating speed and gap, relying on the operator's skill and experience, suitable for exploratory experiments with many variables. If high reproducibility is needed, such as for batch preparation of comparative samples, consider models with numerically controlled pushers. Set the speed and travel distance, press a button, and the machine completes the pass consistently, offering greater stability than manual operation.

Minor details determine how "user-friendly" it is. Is the machine heavy? A sturdy frame minimizes vibration for more even coatings. Is it easy to clean? Dried slurry can be difficult to remove, so easy disassembly and cleaning of the blade and stage are important. Are there accessory tools? Items like spacers of varying thicknesses or different coating molds can significantly expand its application range.

Therefore, when browsing "Huinuo" products on the Nanbeichao mall, don't focus solely on images and price. Pay close attention to the product descriptions for "coating thickness range," "coating method," "stage type," and "control method," and match these specifications with the material properties you handle daily in the lab.

Ultimately, this machine is an extension of your hands. Choosing the right one makes it a silent, reliable partner, helping you materialize the layers of material conceived in your mind onto the substrate. Choosing poorly may relegate it to a corner as a "somewhat inadequate" device. Consulting senior lab members about their preferred models or reviewing the configurations used in your research group's seminal literature are usually reliable approaches.

This exemplifies the principle of "a craftsman must sharpen his tools to do his work well"—and the blade coater is no exception.