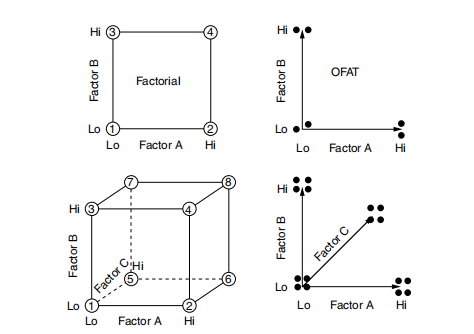

Traditional experimental methods change only one process factor (OFAT) or one ingredient in the recipe at a time. However, the OFAT method does not provide data on the interaction of factors (or ingredients), which are likely to occur in paint formulations and processes. Statistics-based Design of Experiments (DOE) provides a validated model, including any significant interactions, enabling you to confidently predict response measures as a function of input. The payoff is identifying the "sweet spot" where you can achieve all your product specification and processing goals.

DOE's strategy is straightforward:

1. Use a screening design to separate important few factors (or components) from trivial many factors.

2. Follow-up through in-depth investigation of survival factors. Generate a "response surface" map and move the process or product into place.

However, the design needs to be adjusted according to the nature of the variable under study:

Ingredients in Product Formulations

Factors Affecting Process

Traditionally, experimentation with recipes and processes has been carried out separately by chemists and engineers. Clearly, the importance of collaboration between the two professions to the success of any research cannot be overstated. In addition, mixing components can be combined with process factors into a design for ultimate optimization. In other words, you can also mix your cake and bake it, but this should only be done at the very end of development - after you've narrowed down the variables to a handful of variables of undeniable importance.

We will spend most of this brief discussion on process screening, as these designs are relatively simple, yet very powerful for making breakthrough improvements. Mastering this level of DOE will put you ahead of most technical professionals and pave the way to better tools for optimizing a process or formulating a product.

Figure 15.1 Comparison of two-level factorial design (left) and OFAT (right) with two factors (top) and three factors (bottom)