Most common solvent vapors can be oxidized and converted to clean and harmless carbon dioxide and water vapor. However, chlorinated solvents produce the offensive hydrochloric acid which evaporates upon oxidation.

Thermal oxidizers typically operate in the 1200 to 1500°F range with a hot gas retention rate of 0.3 to 0.6 seconds to achieve substantially complete oxidation of organic material.

Catalytic oxidizers typically operate several hundred degrees cooler than thermal oxidizers, depending on the specific catalyst used and the concentration of oxidizing vapors.

More expensive noble metal catalysts, such as platinum, can withstand temporarily higher temperatures than less expensive catalysts that are susceptible to thermal deactivation. Some impurities in the air may poison any catalyst.

In some cases, the heat energy released by steam oxidation can be used to heat process dryers or ovens. Usually, the high temperature gas from the oxidant is used to preheat the cooler steam- filled air and the waste heat is still sufficient to meet the process needs.

The cost of oxidizing a given amount of vapor depends on how much dilution air is present, or, for a given amount of air, how much vapor is present. More air requires a larger incinerator to keep the hot gases in the minimum time required to complete the oxidation reaction, and more energy is required to bring the air to combustion (oxidation) temperature.

However, if the vapor concentration is maintained near 40% LEL or above, the solvent vapor may provide nearly all of the energy required. At lower concentrations it becomes increasingly necessary to provide an auxiliary fuel or to provide more air-to-air heat transfer to preheat the steam laden air.

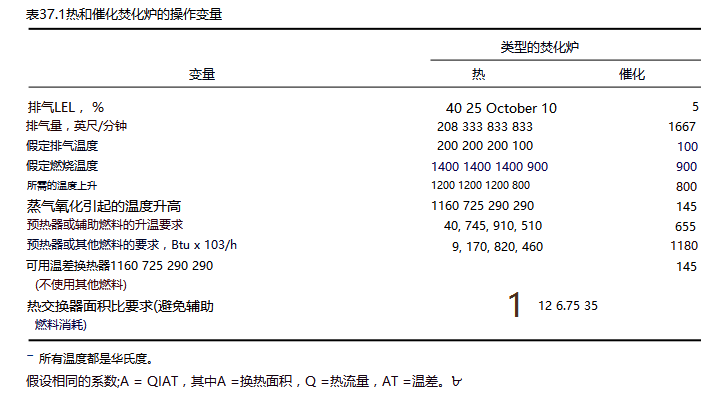

For example, one cubic foot of toluene vapor incinerated more or less diluted with air in the exhaust stream is shown in Table 37.1.

From Table 37.1 it can be seen that a reduction in gas flow (for a given solvent vapor flow) will proportionally reduce the size of the steam incinerator, but the size or number of heat exchangers required for refueling is affected to a greater degree.

It is theoretically possible to provide enough heat exchanger capacity to avoid the need for additional fuel for normal operation. In practice, an auxiliary fuel burner is required for start-up and needs to remain lit and ready to heat the air when the vapor concentration decreases. Heat exchangers for steam thermal oxidizers are usually shell and tube, using stainless steel tubes or ceramic beds. Some metal plate exchangers are also used, but in each case it is important to prevent the steam laden air from leaking or short-circuiting into the exhaust, or bypassing the combustion zone. Such leaks or bypasses can produce offensive odors from partially oxidized organics.

Ceramic bed heat exchangers alternate heating and cooling by periodically reversing the direction of flow through at least two or more beds. The outgoing hot combustion gases flow through a bed until the ceramic piece reaches a set temperature, then the flow is reversed and the steam laden gases are heated so they flow through the hot bed into the combustion zone. There is no problem if the steam laden gas ignites in the bed before the combustion space, but before the flow is switched back, it is good practice to first purge the steam laden gas in the cooking bed into the combustion area. Unoxidized vapors should not exit with the exhaust stream. The bed is relatively large, practical (but not cheap) to provide the high heat transfer area needed to accommodate the relatively lean steam flow. The required bed size can be minimized by high frequency flow switching; the airtight damper can be switched every few minutes. Ceramic sheets need to be selected to withstand frequent temperature changes and accommodate the thermal expansion-contraction cycles that occur. If dust is released due to thermal movement or abrasion, it may prevent direct use from residual heat in the dryer and oven.

Metal surface heat exchanger with hot combustion gas on one side and cooler steam carrier gas on the other, operating continuously without reverse flow or damper switching. Thermal expansion-contraction can be a problem, causing welds to tear or break, and leakage of higher pressure steam laden air into the low pressure oxidation discharge stream. Such leaks can produce an offensive steam burnt smell.

In a shell and tube heat exchanger, longer tubes with baffles on the tubes are more efficient for counter flow than short tubes for cross flow.

A new development patented by Wolverine solves the expansion problem of long tube heat exchangers; one end of the tube is free to expand and contract internally to act as a slide tube for the air aspirator. In this arrangement, a small amount of low pressure oxidation allows steam to leak back into the oxidation zone; leakage in this direction is acceptable.