Dip coating is a simple yet effective technique widely used in manufacturing in different industries. During research and development, it has become an important coating method for the manufacture of thin films using a dedicated dip coater. When the process is optimized, dip coating can be used to produce highly uniform films. Remember: Critical factors such as film thickness can be easily controlled.

One of the advantages of dip coating compared to other processing techniques is its simplicity of design. It is inexpensive to set up and maintain, and can produce films with extremely high uniformity and nanoscale roughness.

Dip coating is a relatively simple technique. However, in order to achieve a greater degree of control when coating substrates, it is important to understand what factors can affect your results. In order to make high-quality films, parameters such as exit speed need to be optimized. Atmospheric factors including temperature, air flow and cleanliness also have a large impact on film quality and need to be closely monitored during dip coating. As with other methods, flaws can occur, but by knowing the root cause, it is relatively easy to find the source of the problem and take appropriate action.

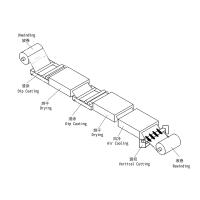

Dip coating involves the deposition of a liquid film by the precise and controlled removal of the substrate from solution using a dip coater. The dip coating process requires a minimum of four distinct steps (or stages), followed by an optional fifth curing step:

immersion

Residential

quit

drying

curing (optional)

All these stages are required in the dip coating process. However, the two critical points that determine the properties of the deposited film are the extraction and drying stages. During these stages, the final film thickness is determined by the interplay between entrainment, drainage and film drying:

viscous flow

drainage

Capillary

Transitions between each of these protocols occurred at different values of extraction speed and solution viscosity. The combination of the three coating schemes ultimately determines the "thickness versus withdrawal speed" behavior of the film. By summing the contributions of the drained state and the capillary state, an equation can be obtained that accounts for the thickness extraction velocity relationship over a wide range of velocities. This also allows us to determine the smallest possible thickness that the solution can be applied to.

Lower the substrate into the solution bath until it is mostly or completely submerged. A short delay occurs before the substrate is removed. During withdrawal, a thin layer of solution remains on the surface of the substrate. Once fully withdrawn, the liquid in the film begins to evaporate and leaves a dry film. For some materials, a further curing step can be performed to force chemical or physical changes in the deposited material.